Hello! Yes, it's been a while. Let's catch up.

|

| I had the opportunity to attend Mass at St. Mary's Cathedral prior to testifying. |

I'm fresh in from Austin where I testified, as did the majority of those who testified,

AGAINST House Bill 3074. What is this bill? Read the text

here and follow its status.

Now, to warn you, there is a committee substitute that was offered, but it has not been released to the public yet. I have read it and my testimony was based on the substitute. It was no better.

HB 3074 is basically a narrower version of SB 303 from last session, if you will. (And, there are the same moral problems with it as well. I have already written about that a great deal in prior posts.) HB 3074's proponents, among them certain "pro-life organizations" and the Texas Catholic Conference of Bishops, say that it would prohibit doctors and hospitals (who can affirm a doctor's decision to terminate this life-sustaining care) from withholding artificially administered nutrition and hydration. The problem is that the exceptions where AANH can be withdrawn are so broad, that the bill immediately takes away any alleged protection that its proponents says it offers. In short, it is a net ZERO gain for the patient.

What it would do is codify into law what doctors and hospitals are already doing, that is, basing their withdrawal of care, including AANH on "quality of life decisions." That is, the doctor and hospital will decide that their opinion is that the patient has no quality of life and that he's basically, "better off dead." That is the net result of what they do. Don't believe me? Read on.

Now, some proponents claim that doctors do this - perhaps in their view, only do this - when the doctor's conscience is troubled by continuing care that the doctor deems is causing more harm than good to the patient. My experience is that that is not the case. In the case I worked on recently, the doctors never talked about their consciences being troubled or that the care being offered was doing more harm than good to the patient. They only said that his quality of life was poor and care should be withdrawn.

But, for the sake of argument, let's suppose there is a case (and they can happen, although the circumstances are very specific and therefore a tiny percentage of these cases), that a person's condition is so very poor that his body can actually no longer assimilate nutrition and hydration anymore - perhaps his stomach or lungs are filling with fluid because his body simply cannot digest or process the nutrition. In that case, AANH is doing more harm than good. It would be morally legitimate to withdraw it. Bishop Gracida has recently

written about this.

Let's say that the family is not ready to make that decision and the doctor's conscience is truly being pained by continuing this care. Or, let's say that there are situations, like the situation I describe below, where there is no harm in providing the AANH to the patient, but let's pretend that the doctors had conscientious objections to continuing any care for this patient anyway. What happens in this situation in Texas? The doctors say they want to withdraw care. If the family objects, they get a hospital ethics committee hearing, which usually rubber-stamps the decision of the doctor. Care can then be withdrawn in 10 days unless the family finds another facility.

If a doctor does not want to continue care - for whatever reason - in Texas under law he can choose to withdraw life-sustaining care and kill the patient. Why must it be that way to "protect his conscience"? Why not just transfer the care of the patient to another doctor or facility? Why this process whereby you have an unreasonably short deadline to transfer the patient because a doctor has decided this life is not worth saving? Conscience can be protected without killing a patient. I recently put this question to a doctor that advocates for this system and she never responded with an answer. There is no answer. It's absurd but with deadly results.

Back to HB 3074. Besides my written testimony, I also testified verbally and it varied some based on what had been said before me and questions I had heard the committee members ask. Many testified about this bill. By our count, a significant majority were against. You can see the entire State Affairs Hearing

here. Scroll down to the 4/15/15 hearing that began at 12:25 p.m. Click on "State Affairs" and the video will start in another window (which is why I cannot give you a more direct link). Then you can just "fast forward" to the start of our particular bill.

There were several bills heard that day. The testimony concerning HB 3074 starts at 4:40 (that's 4 hours, 40 minutes.) It is worth your time - especially if you are going to advocate for or against this bill - to watch the entirety of the testimony. It goes until 7:46. My testimony is at about 6:12.

Many, many dedicated, faithful, and smart people testified against this bill and I am so honored and proud to know them. Many have become my very good friends over the last two sessions and I am thankful for them. Again, watch all of the testimony. Each person testifying against had very good points to make and made them in different ways that shed more and more light on the substance of the bill and it's problems.

For those wondering, yes, there are

good bills introduced that would amend TADA in substantive ways.

- HB 2949 by Representative Stephanie Klick & SB 1546 by Senator Charles Perry is a DNR Consent Bill - that is, you would have to give your consent prior to a "Do Not Resuscitate" Order being put in your file. That is not the law currently. DNRs are slipped into patients' files without their knowledge or consent. This allows the hospital to NOT resuscitate a patient. How about that?

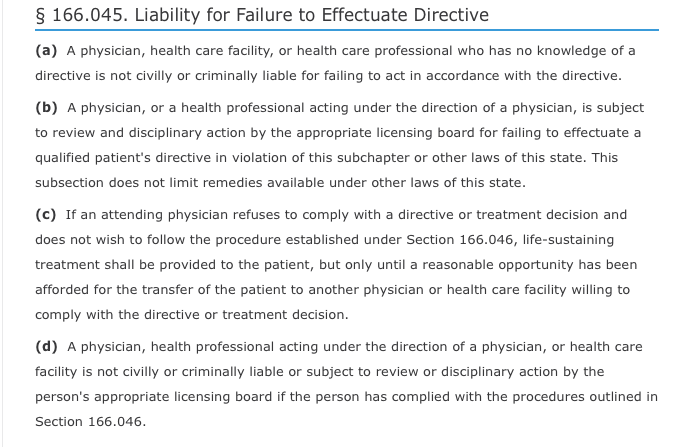

- HB 3414 by Representative James Frank & SB 1163 by Senator Kelly Hancock. This reform to current law (Chapter 166.046 of the Health & Safety Code) would limit the statutory ethics committee process to only be used to withdraw treatment that is physiologically futile. This bill would also clarify that treatment decisions cannot be based on discriminatory judgments against persons with disabilities, the elderly, and terminally ill patients.

However, these bills have not been set for a hearing at this time and time is running short in the session. Only the powers that be in the Texas Legislature can set the bills for hearing....

But know this - just passing anything will not do. The chairman of this committee made it abundantly clear that he just wants to get it over with and not have to return to this issue each session. (For the record, this particular individual is not the only person addressing this issue. Each session the committee make-up changes. Each session these bills are assigned to different committees. But his statement was telling and we should take heed.) There was much talk about "incrementalism" and isn't this just a little better than the status quo? No, it's not. But at least this committee chairman wants to "just do something" to say that it's been done and not deal with it again. That tells me that just passing something that is inherently flawed and "fixing it later" is not politically feasible. The legislature will just tell us later that "the matter has been dealt with." Remember, TADA has been a deeply flawed law for about 15 years. It has not yet been amended to address these flaws yet, although efforts are made each session. A poor effort is a wasted effort - especially when the poor effort changes nothing.

And with that lengthy introduction, here is my written testimony.

Testimony in Opposition to HB 3074

(and the Committee Substitute)

By: Kassi Dee Patrick Marks, JD

I submit this written

testimony in opposition to this bill. In the simplest of terms, it is

meaningless as reform. As with the current state of the Texas Advance

Directives Act, there are still no patient rights protections provided in this

bill, there is still no due process for the patient or his or her family, and

there is absolutely no enforcement mechanism to make sure even the meager,

largely symbolic (and inconsistent) changes (but I would not call them reforms)

are followed. I cannot see how this bill would prevent patients from being

starved or dehydrated to death – including during and after the 10-day

deadline – to find a new facility.

The reform of TADA is

needed and necessary. Recently, I attended a medical ethics committee hearing

at a hospital. I sat through more than an hour of “testimony” where three

doctors explained why they wanted to end the life of an ill patient before a

board that rubber-stamped their decision. The family sat and listened to the

doctors repeat at least a dozen times variations of: “He has no qualify of

life.” The doctors had no stated or implied conscientious objections to continuing

care; they just simply did not see the point in continuing to care for this

patient. Meanwhile, the patient’s family pleaded for more time for their

patient to respond and to find another facility. On that day, it fell on deaf

ears. Among the things said to the family by the doctors were the following,

and these are direct quotes:

- “In nature, when people are immobile this long, they get eaten.” Stated

by the neurologist advocating for the termination of this patient’s care and

life.

- “What we are saying is his quality of life will never change.” Primary

doctor recommending termination.

- “The person Mr. ___ was is gone because that resides in the brain and

that is gone.”

- “The person is not going to return.”

- “The real action is the person he was…that person is gone and is not

coming back.”

Because this person had a

poor prognosis at becoming the person he was, the doctors did not want to give

more time. This is despite the family reporting seeing improvement, such as

turning toward sounds, being startled when something fell and made a loud sound,

and sobbing when the doctors discussed amputating his leg in front of him and

his family. All of this was dismissed as reflexes by the doctors who proceeded

to make the comments above, among other things. This is also despite the

growing record of cases where patients recover from a PVS or comatose state years later. The brain does recover. It

just needs time.

The doctors also refused

to consider in home care for the patient. When the subject was broached, they

were silent – they were unprepared for that. Then they all quickly said that

was “not in the best interest of the family or the patient” without stating why

except for resorting back to the “quality of life” mantra.

I relay this experience

to make clear that TADA must be reformed. But it must do so in a way to prevent

this sort of thing from being so commonplace. And, it is commonplace. No one

among those that are promoting this legislation has ever worked through a

medical ethics committee hearing and helped patients navigate this process which

is stacked against them.

The substituted version contains

changes to Section 5, which would amend Section 166.046(e). While it purports

to restrict the withdrawal of artificially administered nutrition and hydration

(“AANH”), the vast array of subjective exceptions included, leave this goal

unmet.

Which definition of the

term is intended by this bill? The ramifications are important for the patient

whose very life depends on it. This provides yet more uncertainty to this

legislation, and rather than solving problems, creates more.

But beyond that, if the purpose

of this bill, and this language specifically, is to restrict when doctors can withdraw

AANH – how does it in actuality do that?

Who is going to make sure

that the doctor has actually determined that AANH is contraindicated for the

patient because continuing it will “seriously exacerbate other major medical

problems not outweighed by the benefit of the provision of the treatment”? What

constitutes an exacerbation or a major medical problem? Those are undefined

terms. And would the treatment have to exacerbate more than one major medical

problem? The language is plural. If it only exacerbated one major medical

problem, is the patient saved from starvation and dehydration? The

problems with this bill are legion – even after the revisions.

Another reason the second

exception cannot be supported is that it begs the question of why there is a second

exception at all when the first exception addresses hastening death of the

patient by continuing AANH, which would be a far more restrictive provision.

But there is still no enforcement mechanism to ensure that these exceptions are

applied correctly.

This third exception

concerning “irremediable physical pain or suffering not outweighed by the

benefit of the provision of the treatment” is likewise just as problematic. The

doctor determines what he cannot possibly know. What level of pain the patient

is in can only be known by the patient and whether he is willing to tolerate

the provision of AANH to sustain his life should be up to him or his

surrogate/family member. This exception continues to allow doctors to make

“quality of life” decisions for patients and terminate their lives against

their will.

The fourth exception

contains the terms “medically ineffective at prolonging life” in the context of

the provision of AANH. If the patient has a serious illness and is terminal,

then the provision of AANH is not going to cure his illness. It would be

ineffective at prolonging his life when compared to the underlying illness. But

withdrawal of AANH will hasten a patient’s death and could, even for a terminal

patient, ultimately be the cause of death.

This exception is extremely problematic because a doctor can always say

that given the patient’s condition, AANH is not going to be medically effective

at prolonging his life because of his condition. It is a Catch 22 for the

patient and a provision open to abuse.

Again, for this entire

bill, as with TADA itself, there is no enforcement mechanism to make sure that

these exceptions, even as reworded, are not abused and used for termination of

ill/disabled people based on what really amounts to a doctor's determination

of whether the patient has a "quality of life" that the doctor

deems acceptable or not. Why is the patient/family surrogate not the person

making this life and death decision? That is still a foundational problem with

TADA that this bill does not even attempt to remedy.

Finally, the new language

added to Section 6 which would amend Sections 166.052(a) and (b), which is

paragraph numbered 3, creates an internal contradiction or inconsistency with

paragraph 5. The new language in paragraph 3 says the facility will continue

AANH after the 10-day period unless the same problematic exceptions apply, but

then paragraph 5 still says that if a provider cannot be found within 10 days

it may be withdrawn unless the family gets a court order. If the purpose of this

bill is truly to prevent withdrawal of AANH, paragraph 5 takes that away. This

is very important. (It is reminiscent of the bait and switch used last session

with regard to SB 303. First, proponents of it included language giving the

patient 21 days to find a new facility, then by the end of the proceedings, the

substitute bill had the deadline back to 10 days.)

This bill amounts to no

reform at all. It is a wasted effort when there is already good legislation

introduced which addresses these issues in meaningful, substantive ways. Patients’

lives are at stake and any reform efforts undertaken must be real.

Thanks for reading!!